The information on biodiversity and forest impacts from mining in this blog is mostly taken from the 2022 Theme 2 Assessment on Sustainable production and development. Please refer to the full report for more information.

In 2019, a UN report described a global biodiversity crisis with an unprecedented rate of animal and plant species extinctions and one million species at risk of extinction. Nonetheless, the biodiversity crisis does not receive nearly as much media and political attention as the climate crisis. This is despite the fact that both crises need to be tackled together: Protecting habitats like forests, for example, can both maintain species richness and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions by pulling carbon from the atmosphere and storing it as biomass.

Starting today, governments are meeting in Montréal, Canada for COP15 to negotiate targets on preventing biodiversity loss through 2030 under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Policymakers at the recent UN climate conference, COP27, called for concluding a “Paris Agreement” on biodiversity at COP15 emphasizing that limiting global warming to 1.5°C is impossible without protecting and restoring ecosystems including forests.

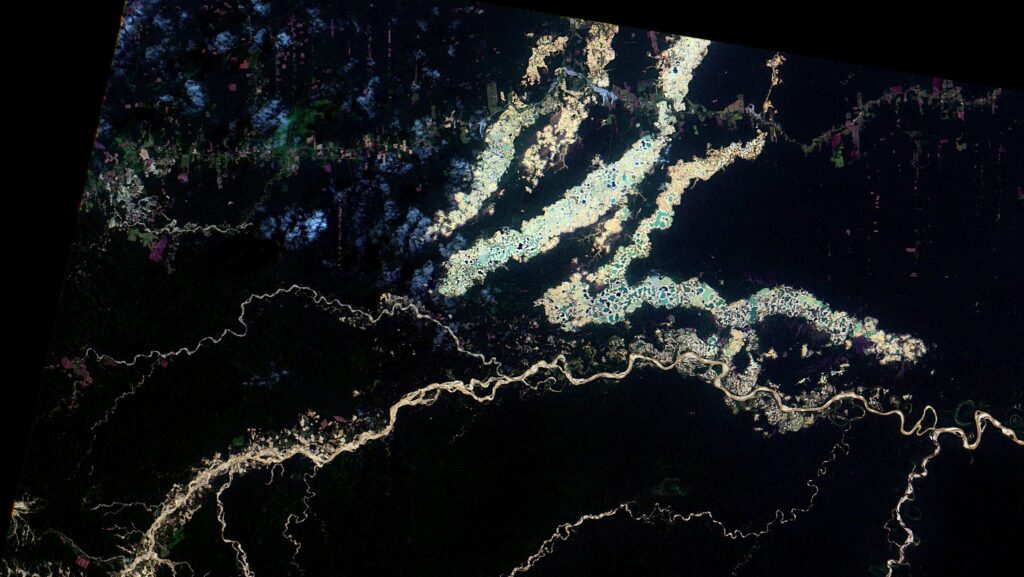

The mining sector is an important player in both the climate and biodiversity crises, but it has received relatively limited attention in international conversations of these topics to date. The 2019 UN report highlighted that even though less than 1% of global land is used for mining, the industry has significant negative impacts on biodiversity. This is mostly due to the indirect impacts of mining: Mining can support local population increase that drives expansion of infrastructure and economic activities with risks for local ecosystems. For example, mining indirectly contributes 9% of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. At the same time, mining will play an essential role in climate change solutions, as renewable energy technologies rely heavily on mined metals and minerals found in many forested areas.

Progress made: Mainstreaming biodiversity and forests into the mining sector

Based on commitments related to the CBD, both public and private sector have made progress in mainstreaming biodiversity into mining policies and practices that rely and have an impact on ecosystems and their services.

Public sector regulations:

Most countries have regulations in place to reduce biodiversity impacts from mining industry investments. Requirements for environmental and social impact assessments, mine closure and rehabilitation, and biodiversity offsetting provide tools for mitigating forest and biodiversity harms from mining operations. However, often these regulating policies are poorly designed and do not reflect best practice in avoiding biodiversity impacts. Even where policies are adequate on paper, enforcement may be lax.

Designating protected areas is another potential tool to mitigate ecosystems encroachment by mining activities. However, many countries carve out exceptions to these restrictions for the industry, and recently many protected area restrictions have been loosened to stimulate economic recovery in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, much mining remains illegal, especially in protected areas, and is therefore not yet adequately addressed by government enforcement nor covered by public sector regulations.

Private sector commitments and policies:

In response to investor demand, most mining companies have now adopted some form of corporate social responsibility (CSR) or environmental, social, and governance (ESG) approach to guide their activities. Biodiversity commitments and policies are relatively common in these principles. For example, 26 out of 38 mining companies that reported through CDP in 2021, had made a public commitment to reduce or avoid impacts on biodiversity. The majority of these companies had company-wide commitments, rather than commitments targeting only specific mines or geographies.

Fewer companies, though, pledged to adopt the mitigation hierarchy approach (a decision framework which allows for the systematic consideration of negative biodiversity impacts and mitigation options), not to explore or develop mines in World Heritage sites, or to aim for a Net Positive Impact on biodiversity.

The 26 mining companies with a public biodiversity commitment also have a documented, publicly accessible biodiversity-related policy to manage impacts from their operations. A further four companies report that they have a biodiversity policy that is not publicly available, while seven more plan to develop a biodiversity-related policy by the end of 2023. That leaves only 1 out of 38 companies with no plans to have a policy in place by 2023.

While some company policies reiterate an awareness of the importance of natural habitats and commitments to good practices, others provide more detail by setting timebound targets or describing biodiversity-related performance standards. Overall, almost half of the policies contain the kind of explicit commitments or references to best practices that characterize well-designed, effective policies to reduce negative biodiversity impacts.

The Responsible Mining Foundation (RMF) has tracked mining company performance since 2018 against four indicators of “responsible mining:” meaningful integration of ESG throughout the business model, transparency and data-sharing, a proactive rights-based approach to harm prevention, and international action to promote responsible mining. Each of these indicators also serve as necessary, though not sufficient, building blocks for forest-positive mining. Against these measures, the RMF has found slow improvement by assessed companies, which cover 25 to 30% of global mining production. Companies improved by an average of 17% from 2018-20, and 11% from 2020-22. The evidence shows that progress by companies that have traditionally been leaders on responsible mining is slowing down – top tier companies only improved by an average of 4% from 2020-22.

Voluntary sustainability standards:

Twelve of the 20 largest international mining companies have joined or adopted voluntary sustainability standards. The International Council on Mining and Metals’ (ICMM’s) Mining Principles have the greatest representation: With 12 of the 20 companies as members, ICMM companies now cover 30% of global mining production.

The Mining Association of Canada’s Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) framework is the second-most adopted standard, with seven members. The TSM framework has taken a unique approach to adoption, targeting national industry bodies rather than individual mining companies. To date, the TSM framework has been adopted by nine countries’ national mining associations, covering 26% of global mineral and metal production value.

Two of the top 20 companies have adopted the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA)’s Standard for Responsible Mining, which explicitly calls for the identification of direct, indirect, and cumulative effects on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Meanwhile, the number of mine sites participating in IRMA has increased over four-fold in the last two years. As of September 2022, 23 mine sites across 19 companies are registered on the IRMA Engagement Map (previously Responsible Mining Map), an increase from 5 in 2020. At least 13 of those sites have begun or completed an independent, third-party assessment.

Only a few mining sector standards—including IRMA’s Standard for Responsible Mining, the IFC’s Performance Standard, the Responsible Jewelry Council’s Code of Practices, and to some degree the Aluminum Stewardship Initiative’s Performance Standard—require mine site operators to consider indirect and cumulative impacts on biodiversity in addition to direct effects, reflecting best practice in accounting for and mitigating forest risk.

Opportunities to act: Strengthening a biodiversity framework for mining at COP15 and beyond

While progress has been made in mainstreaming biodiversity into policies and practices in the mining sector, both governments and companies can and must do even more.

Government opportunities:

Government regulations should mandate that biodiversity risks identified for any development project must be managed by applying the mitigation hierarchy, with the first step – avoidance – applied as much as possible, while accounting for other priorities for sustainable development. Governments should also enforce strict “no-go” zones for the mining industry in high-value ecosystems. This also applies to illegal mining in protected areas.

Governments should also strengthen the regulatory processes for prospecting, exploring, and licensing mining activities. Issuing mining licenses should be made contingent on mitigation planning. Environmental and social impact assessments should be required to be conducted early in the mining life cycle and to assess indirect and cumulative project impacts.

Countries should also consider the 10 Point Plan for Financing Biodiversity that was recently discussed and endorsed by 17 countries at COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. Implementing the plan will bridge the global biodiversity finance gap by unlocking funding for protection, restoration, and sustainable use of biodiversity.

In a submission to the CBD’s post-2020 framework on mainstreaming biodiversity, ICMM suggested various measures that would strengthen global and national policy including:

- Public-private collaboration including at the landscape-level;

- Corporate engagement in policy discussions;

- Enforcement of robust minimum requirements;

- Business integrity requirements and best practices;

- Enforcement of regulations on World Heritage sites and in protected areas;

- Biodiversity-inclusive Environmental and Social Impact Assessments and Strategic Environmental Assessments;

- Environmental offset policies with embedded biodiversity-specific components;

- Establishment of national level strategies and targets on biodiversity to which businesses can contribute; and

- National and global biodiversity databases for corporate data-sharing.

Companies' opportunities:

Companies need to urgently increase the scope and stringency of corporate action, whether voluntary or mandated. In addition to their relatively low direct impact, mining companies need to consider their indirect influence through opening up ecosystems to other drivers of habitat destruction (e.g., through access roads to mines). Companies who wish to lead should advocate at local, national, and international levels for holistic approaches to addressing biodiversity impacts; approaches where corporate action is enabled and supported by appropriate legislative and policy frameworks, trade standards, and financial instruments and incentive structures.

Mining companies, and those sourcing from them, should adopt biodiversity commitments and policies that explicitly state that biodiversity impacts from company operations at and beyond the mine site, and company-wide, must be addressed using the mitigation hierarchy. They must then embed the necessary processes and mechanisms in their standard operations to realize these commitments, including monitoring and reporting systems. Companies should rely on existing good practice guidelines such as the Mitigation Hierarchy Guide or Good Practices for the Collection of Biodiversity Baseline Data of the Cross-Sector Biodiversity Initiative. Finally, companies should implement appropriate site-level screening of their biodiversity impacts and respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples (IPs) and local communities (LCs).

Mining sector sustainability schemes should require site operators and downstream purchasers to assess and manage not just the direct biodiversity impacts of extraction, but the indirect and cumulative as well. Companies in the mining supply chain should also consider the opportunities of conducting biodiversity conservation and restoration activities, through a nature-based solutions lens, to mitigate business risks, achieve company climate and biodiversity targets, and provide benefits to affected stakeholders.

In April 2023, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development will publish a new Handbook for Environmental Due Diligence in Minerals and Metals Supply Chains. This tool will help downstream companies use their leverage to better know and address the environmental impacts of mining, and mineral processing and transportation. Companies should use the tool to build the identification and management of environmental risks into the scope of their supply chain due diligence policies and management systems; self-assess and monitor the effectiveness of their environmental risk management systems as applied to their supply chain; and to publicly report in a meaningful way for external stakeholders and provide assurance to investors and others on their environmental risk management processes and adverse impacts.

Investor opportunities:

Investors can use their financial leverage over mining companies to push businesses towards reducing biodiversity harms. So far, for example, investors have been active in relation to tailings storage and have created the Investor Mining and Tailings Safety Initiative. Looking forward, investors can pressure the adoption of comprehensive sustainability standards. Investors can also support initiatives to reduce the environmental, social and/or governance risks of finance, such as the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), a voluntary and aspirational set of principles that were developed with the objective to contribute to a more sustainable financing sector.

Overall, there are many opportunities for action around COP15: Governments can mandate transparency and disclosure or due diligence in relation to biodiversity, engage stakeholders, and increase public-private collaboration, especially at the landscape level. Companies can use data to understand their biodiversity impacts throughout the value chain; increase their compliance, ambition, and speed; channel finance towards biodiversity protection; and push the public sector towards improved respect for human and IP and LC rights.

Governments and companies can benefit from favorable conditions for meaningful action: the voices calling for stronger action to protect climate and biodiversity are growing in number and volume by the day.

Featured image: Large scale illegal gold mining at Southern Peruvian Amazon, at Madre de Dios. Author: Oton Barros (DSR/OBT/INPE), from Coordenação-Geral de Observação da Terra/INPE via Flickr